Local origami artist Kathy Knapp has shared the joy of paper folding for nearly 30 years.

Her hands move quickly as she deftly folds a small purple square of kami paper. She’s demonstrating how to make a paper crane, perhaps the most recognizable form of traditional origami. She rotates and flips and folds, explaining her movements as she goes—and how the crease pattern is the same as that of the German bell. In a matter of minutes, she holds the completed orizuru in her hand, a delicate manifestation of paper-folding magic. It might seem unusual that a Peoria native would become a renowned expert in an art generally associated with Japanese culture, but that’s just what Kathy Knapp has become.

First Folds

Her earliest encounters with origami were sporadic. Like many schoolchildren, Knapp made gum wrapper chains, paper airplanes and cootie catchers on the playground, and she remembers someone coming to her classroom to teach the German bell and the German star. “The mountain and valley folds were not stressed at all, so I just always hinge-folded everything,” she recalls. “I could do the bells [at] different sizes, and I made ornaments out of them.”

After earning a nursing degree from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1969, Knapp worked as a nurse at Zeller Mental Health Center and for Caterpillar before starting a family with her husband, Gary. As they raised their three children, origami kept popping into her life: her son showed her how to make a crane after he learned at Vacation Bible School, and when her youngest daughter needed to create a paper Noah’s Ark for a school project, Knapp took her to the library and found some books so they could learn the patterns. “I still didn’t even know the term ‘origami’ at that point,” she admits. Knapp enjoyed helping with the project so much that she bought her first origami book, Paper Pandas and Jumping Frogs by Florence Temko. “It’s still my favorite,” she says, “and I have well over 700 books at this point.”

While volunteering as a nurse at The Sun Foundation’s Art and Science in the Woods summer camp, she spent her free time practicing the models she knew. Her creativity caught the eye of Sun Foundation co-founder Bob Ericksen, and soon she was teaching classes there. Her hobby has since developed into a career that has spanned nearly 30 years and connected her with origami enthusiasts around the world.

Mastering the Craft

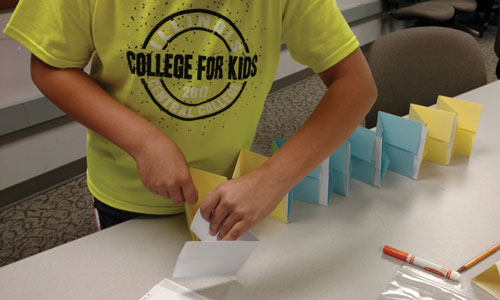

Knapp has taught origami to children and adults throughout central Illinois, at schools, libraries, churches and art fairs. She still teaches at Art and Science in the Woods, as well as ICC’s College for Kids and 4-H Clover Clinics, and she’s worked with children with disabilities and those who are learning English as a second language. She starts with the fundamentals before progressing through more difficult patterns, and has even developed her own stories and games to help her students remember the folds. Ten years ago, she founded Origami Peoria Area (OPA), a monthly gathering for area folders, and in 2010 she received the Ranana Benjamin Award, established by Origami USA to honor outstanding origami teachers of children.

Each year Knapp looks forward to attending the CenterFold Origami Convention in Columbus, Ohio for the opportunity to meet other folders and share techniques. “It was a little unnerving that first time… because there are people there whose books I have!” she notes. She reveres the masters of her craft and is still in awe that she would be considered anywhere near their level of expertise—even as she edits diagrams for other artists and publications for the British Origami Society, and recently assisted with editing a book. She also folds pieces for commission and has received some interesting requests, from making a ring out of a $100 bill to a gig at an agriculture event in Iowa folding stalks of wheat out of dollar bills.

Knapp loves origami for its accessibility. “You can do it anywhere with just a piece of paper and your hands; you don’t need fabric, needle and thread, or paintbrushes,” she explains. “You just fold with what you have.” Anyone can do it, and any scrap of paper can be transformed. She’s made cranes from paper as small as a square inch, contributed to a life-sized paper replica of Jabba the Hut, and used everything from lace to potato chip bags to make her creations. Perhaps most remarkable, Knapp swears she’s only gotten a single papercut in all her years of folding. “And that was just from opening a ream of paper!” she laughs.

Beyond Aesthetics

The beauty of origami is that it can be traditional or experimental, simple or complex; it has its own language and rules, combining art and mathematics. “It’s all math,” Knapp declares. “The geometry and algorithms result in finished art forms that are truly beautiful.”

The principles of origami have been utilized in everything from retinal implants, heart stents (from which her husband has benefited) and biomedical nanodevices to airbags in cars and solar panels in satellites. Engineers are using origami techniques to strengthen materials and make robotic “muscles” that can lift 1,000 times their own weight, while architects are implementing folding mechanisms to design easy-to-assemble homes and energy-efficient shading and cladding for buildings. And the functional applications of folding are sure to lead to other exciting discoveries in the coming years.

The principles of origami have been utilized in everything from retinal implants, heart stents (from which her husband has benefited) and biomedical nanodevices to airbags in cars and solar panels in satellites. Engineers are using origami techniques to strengthen materials and make robotic “muscles” that can lift 1,000 times their own weight, while architects are implementing folding mechanisms to design easy-to-assemble homes and energy-efficient shading and cladding for buildings. And the functional applications of folding are sure to lead to other exciting discoveries in the coming years.

Knapp is fascinated by these possibilities, but for her, the joy of origami comes from sharing it with those around her. Folding is a peaceful practice that provides an opportunity to focus and simply connect with others. To illustrate, she describes how her daughter learned to make a modular kusudama ball from a Japanese girl: “My daughter didn’t speak Japanese and the girl didn’t speak English, but they both spoke origami.”

She explains the tessellation pattern of her necklace—a cherished birthday gift that was hand-folded out of gold-plated brass by an Israeli artist (pictured)—points out different techniquesin one of her many books, and lists off artists who are challenging the traditions of paper art. She loves using the paper napkin rings at restaurants to delight children with jumping frogs as they wait for their meal, and she always folds the tips for her servers into something creative. For Knapp, it’s all about the smile when a student completes a project, or when she slips a treasure into the hands of a stranger. “It’s amazing to see their eyes light up,” she says, adding a smile of her own. a&s